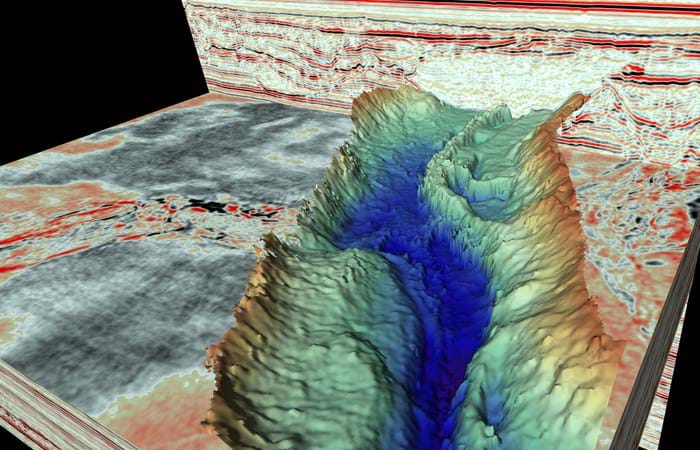

Gardline has produced high resolution 3D seismic data which reveals in unprecedented detail huge seafloor channels - each one 10 times wider than the River Thames.

The data were initially used for hazard assessments at drill sites but it was clear from the outset that the seismic data had far more to offer, particularly in the academic world. The findings (to be published this week in the journal Geology) are ground-breaking and new-to-science for which Gardline are very happy to be associated with.

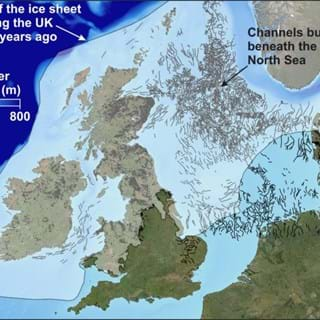

For the first time an international team of scientists can show previously undetectable landscapes that formed beneath the vast ice sheets that covered much of the UK and Western Europe thousands to millions of years ago. These ancient structures provide clues to how ice sheets react to a warming climate.

So called tunnel valleys, buried hundreds of metres beneath the seafloor in the North Sea are remnants of huge rivers that were the ‘plumbing system’ of the ancient ice sheets as they melted in response to rising air temperatures.

Lead author James Kirkham, from British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the University of Cambridge, says:

“The origin of these channels was unresolved for over a century. This discovery will help us better understand the ongoing retreat of present-day glaciers in Antarctica and Greenland”.

Dr Kelly Hogan, co-author and a geophysicist at BAS, says:

“Although we have known about the huge glacial channels in the North Sea for some time, this is the first time we have imaged fine-scale landforms within them. These delicate features tell us about how water moved through the channels (beneath the ice) and even how ice simply stagnated and melted away. It is very difficult to observe what goes on underneath our large ice sheets today, particularly how moving water and sediment is affecting ice flow and we know that these are important controls on ice behaviour. As a result, using these ancient channels to understand how ice will respond to changing conditions in a warming climate is extremely relevant and timely.”

3D seismic reflection technology uses sound waves to generate detailed three-dimensional representations of ancient landscapes buried deep beneath the surface of the Earth. The method can image features as small as a few metres beneath the surface of the Earth, even if they are buried under hundreds of metres of sediment. The exceptional detail provided by this new data reveals the imprint of how the ice interacted with the channels as they formed. By comparing these ancient ‘ice fingerprints’ to those left beneath modern glaciers, the scientists were able to reconstruct how these ancient ice sheets behaved as they receded.

By diving into the past, this work provides a window into a future warmer world where new processes may begin to alter the plumbing system and flow behaviour of the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets.